Noah is a hot topic these days because of the movie with Russell Crowe. Here is some research I’ve done to add to that conversation.

I’ve written a Biblical fantasy novel called Noah Primeval. I’ve researched this topic extensively. Noah Primeval has been a category bestseller on Amazon for 3 years. It’s first in a series of novels called Chronicles of the Nephilim.

Did the Bible Copy the Flood Story from an Ancient Babylonian Epic?

With all the talk about Noah and the Flood, it is inevitable that the old issue would come up about how every culture around the earth has Flood legends. There are even stories like the Akkadian Atrahasis, the Sumerian Ziusudra and the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh that have elements exactly like the Biblical story of Noah.

So, what does all the similarity mean? Did the Bible copy it’s story of Noah from an older myth?

One of the most famous and fascinating myths that find correlations with Noah’s Flood is the Epic of Gilgamesh from Babylonia. Let’s take a look at this epic and see how it compares with the Bible’s story of Noah.

Noah and the Flood in the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is about an infamous Mesopotamian king, Gilgamesh of Uruk, who was a giant and claimed to be two thirds god, one third human (Sound familiar?). It tells the story of how Gilgamesh hungers for meaning and significance and sets out on a journey to find eternal life.

Perhaps the most important connection that the Epic of Gilgamesh has to the Bible is in the presence of a Noah character and his story of the Great Deluge. At the end of Gilgamesh’s journey he seeks out a man Utnapishtim (our Noah) in a distant land because he’s heard Utnapishtim/Noah survived the Flood.

Gilgamesh figures he might wrest from Utnapishtim his secret of eternal life from the gods. But when he discovers that death is intrinsic to human existence and the special gift will never be granted to another human being, he returns to his beloved city of Uruk and finds his final fame in building the mighty walls and city, which will continue after he is long dead.

Scholars have written endlessly on this topic ever since the first translations of the account were available in the late nineteenth century. A comparison of the two stories yields some significant similarities that indicate a common origin, yet some even more significant differences that indicate divergent meaning.

But what about the Genesis story of Noah’s ark? While it is virtually unanimous among scholars that Genesis was written and edited over time using multiple sources, the more extreme view of this has been adopted by the scholarly establishment that has sought to divide the Old Testament, and in particular the Flood story, into contradictory sources that have been woven together from an older “Yahwist” source and a newer “Priestly” source, all with opposing agendas.

This radical view is falling from favor with the advent of literary and form criticism and because of the complete absence of manuscript evidence to support the remote speculation of such radical redaction. (1) What is coming more to light is the genius of composition that exists in the final canonical literary form that virtually defies categorizing of specific sources.

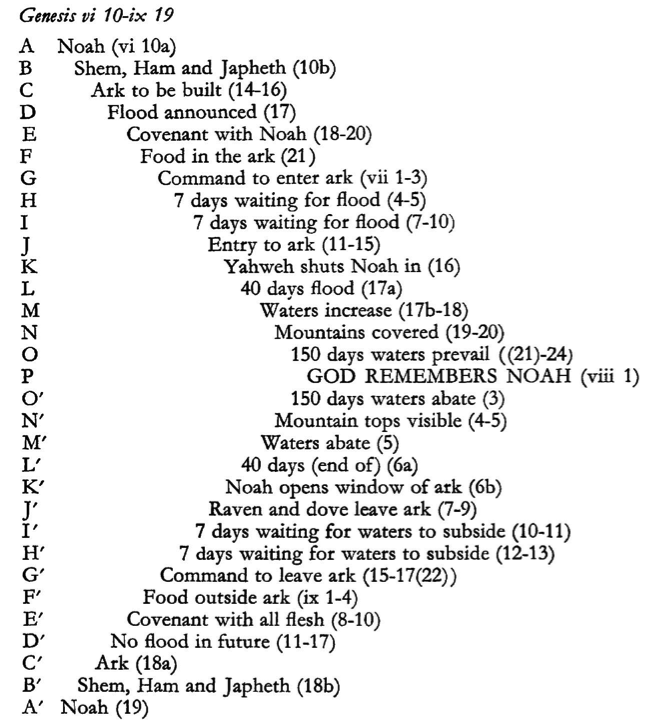

For example, Gordon Wenham has pointed out the complex literary poetic form of “chiasmus” used in the Flood narrative. Chiasmus is a kind of mirroring literary structure that builds the plot with increasing succession, to the middle of the story, where the thematic message is highlighted, only to conclude the second half of the story in a reflective reversal of the first half.

At the risk of overwhelming the reader, here is the literary structure of the Genesis Flood narrative as detailed by Wenham, emphasizing the superior originality of authorship over alleged source material. (2)

Early Biblical criticism tried to reduce the Biblical Flood narrative to a derivative of the Babylonian version, but that theory is now thoroughly discredited. (3) Archaeologist P.J. Wiseman uncovered the existence of a “toledoth” formula in the repeated Genesis phrase, “these are the generations of,” that indicates original source material of inscribed clay tablets rather than a hodgepodge of Yahwist, Priestly, and other contrary sources. (4)Whatever narrative congruity exists between the Bible and the Gilgamesh Epic, their genetic ties are not found in being a derivative of one another.

In my novel Gilgamesh Immortal, while I do write of Gilgamesh visiting Noah and his wife on a distant island, and I do have Noah tell Gilgamesh the story of the Flood, just as he does in the Epic of Gilgamesh, I bring a subversive twist to the scenario. The story that Gilgamesh inscribes onto clay and stone is not the one that Noah told him. Why? Because Gilgamesh is not a repentant follower of Noah’s god, Yahweh Elohim, the God of the Bible. So it would make sense that if he rejects the living God, he would reject the living God’s metanarrative and replace it with his own that would exalt himself or his biased religious construction. So the version we read in the Epic of Gilgamesh today is the deliberately fabricated version of a rebel against Yahweh.

So what is the storyline of the Flood in the original Gilgamesh Epic?

In Tablet XI of the epic poem, Utnapishtim, the Gilgamesh Noah, explains that because of some unexplained sin of man, the pantheon of gods decide to send a Deluge to kill all of mankind. But the god of the waters of the Abyss, Enki (or Ea) defies the decision and sneaks away to give a dream to Utnapishtim, a wealthy man who lives in the city of Shuruppak in Mesopotamia. Through the dream, he tells him to tear down his house and build a large boat to save “the seed of all living creatures.” He gives him the dimensions of the boat and instructions of how to build it.

Utnapishtim is to lie to his neighbors when asked about the large boat by explaining that he is going to move downstream to the city of Eridu. When he finishes the boat, he loads on it all kinds of animals as well as all his extended family members and some skilled craftsman.

The gods then start a storm of wind and rain, led by the storm god Adad, that devastates the land with such force, even the gods get scared and hide up in heaven like frightened dogs with their tails between their legs. The blowing wind and gale force downpour lasts six days and seven nights until “all the people are turned to clay.”

The boat finally runs aground on Mount Nimush, and after seven days, Utnapishtim lets out a dove to see if it can find a perch, but it does not and returns to him. He waits and sends a swallow, and then finally a raven that does not return, indicating enough dry land to get out of the boat.

Utnapishtim then offers a sacrifice to the gods, who “smell the sweet savour” and “gather like flies around the sacrificer.” But when the great god Enlil arrives, he is angry to discover Utnapishtim survived the destruction. When he finds out that Enki had leaked the plan to Utnapishtim, they quarrel. But the crafty Enki denies violating the will of the gods because he did not tell Utnapishtim directly, but through a dream.

Enlil resigns himself to the trickery and decides to bestow immortality on Utnapishtim and his wife, so they would be like the gods, but placing them “at the mouth of the rivers” to dwell faraway from normal mankind.

Utnapishtim then explains to Gilgamesh that the gods will not assemble for his benefit to bestow upon him eternal life. He is destined to die like all humanity. To prove the impossibility, Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh to stay awake for six days and seven nights to prove his worthiness of becoming immortal by exercising power over the stepchild of death: sleep. Gilgamesh cannot do so and he is sent on his way with the consolation prize of finding a magic plant that will restore his youth. As stated before, the serpent then steals that plant away from him.

So, what’s the deal? How does Gilgamesh compare with Genesis? You’ll have to wait until my next post to find out.

Buy the novel Noah Primeval, here on Amazon.com in Kindle or paperback. The website www.ChroniclesOfTheNephilim.com has tons of way cool free videos, scholarly articles about Watchers and Nephilim Giants, artwork for the series, as well as a sign-up for updates and special deals.

FOOTNOTES

1. See Umberto Cassuto, The Documentary Hypothesis and the Composition of the Pentateuch, Skokie, IL: Varda Books, 1941, 2005; Duane A. Garrett, Rethinking Genesis: The Sources and Authorship of the First Book of the Pentateuch, Baker, 1991; John H. Sailhamer, The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition and Interpretation, Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity, 2009; “The New Literary Criticism,” Gordon J. Wenham, Vol. 1, Genesis 1–15. Word Biblical Commentary. Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1998, pp. xxxii-xlii; Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1–17. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990, pp. 12-38.

2. Gordon J. Wenham, “The Coherence of the Flood Narrative,” Vetus Testamentum 28, no. 3 (1978), p. 338.

3. Bill T. Arnold and David B. Weisberg, “A Centennial Review of Friedrich Delitzsch’s ‘Babel und Bibel’ Lectures,” Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 121, No. 3 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 441-457.

4. P. J. Wiseman, D. J. Wiseman, Ed., Ancient Records and the Structure of Genesis: A Case for Literary Unity Thomas Nelson, 1985.

One comment on “Noah Facts #8: Noah Vs. Gilgamesh Smack Down!”

Comments are closed.