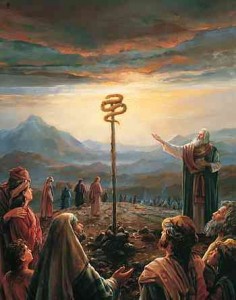

In my novel Joshua Valiant I tell the infamous story of Nehushtan, the bronze serpent, from Numbers 21. As Moses leads the people of Israel through the Negeb desert on their way to enter the Transjordan, the Israelites grumble and complain yet again about their lack of food and water. Yahweh responds by sending serpents to punish them.

Numbers 21:6–9

Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. 7 And the people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord and against you. Pray to the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us.” So Moses prayed for the people. 8 And the Lord said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.” 9 So Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on a pole. And if a serpent bit anyone, he would look at the bronze serpent and live.

The Hebrew word for “fiery serpents” used in this text is seraph, which is the same word used for the winged serpentine guardians of Yahweh’s throne in passages like Isaiah 6:2.[1] There are several different Hebrew words that can be used for serpents, so the choice of this word here should clue us into the deliberations of the writer. While the notion of “fiery” can refer to the venomous sting of a desert snake such as a viper or cobra, there may be more going on here than a mere poetic description of snake bites.

The Hebrew word for “fiery serpents” used in this text is seraph, which is the same word used for the winged serpentine guardians of Yahweh’s throne in passages like Isaiah 6:2.[1] There are several different Hebrew words that can be used for serpents, so the choice of this word here should clue us into the deliberations of the writer. While the notion of “fiery” can refer to the venomous sting of a desert snake such as a viper or cobra, there may be more going on here than a mere poetic description of snake bites.

The picture of seraph snakes having wings shows up in two other passages from Isaiah.

Isaiah 14:29

29 Rejoice not, O Philistia, all of you, that the rod that struck you is broken, for from the serpent’s root will come forth an adder, and its fruit will be a flying fiery serpent.

Isaiah 30:6–7

6 An oracle on the beasts of the Negeb. Through a land of trouble and anguish, from where come the lioness and the lion, the adder and the flying fiery serpent, they carry their riches on the backs of donkeys, and their treasures on the humps of camels, to a people that cannot profit them. 7 Egypt’s help is worthless and empty; therefore I have called her “Rahab who sits still.”

Both of these prophecies against Philistia and Egypt respectively use the idea of a “flying fiery serpent” as a poetic description of the evil or dangerous nature of those nations. Though they are not required to be literal existing creatures for the prophecy to be legitimate, they nevertheless use the same Hebrew reference to fiery serpents that was used in the more historical passage of Numbers describing the “fiery serpents.”

Additionally, the Isaiah 30 passage describes these flying fiery serpents as the beasts of the Negeb, the same location for the fiery serpents of Numbers 21.

Jacob Milgrom argues that the bronze or copper snake that Moses put on the pole was a winged serpent. He concludes this from the link of the Hebrew seraph to the Egyptian uraeus serpent.

Egypt is the home for images of winged serpents. For example, the arms on the throne of Tutankhamen consist of two wings of a four-winged snake (uraeus), which rise vertically from the back of the seat. Indeed, the erect cobra, or uraeus, standing on its coil is the symbol of royalty for the pharaoh and the gods throughout Egyptian history. Winged uraei dating from the Canaanite period have been found, proving that the image of the winged serpent was well known in ancient Israel.[2]

Egypt is the home for images of winged serpents. For example, the arms on the throne of Tutankhamen consist of two wings of a four-winged snake (uraeus), which rise vertically from the back of the seat. Indeed, the erect cobra, or uraeus, standing on its coil is the symbol of royalty for the pharaoh and the gods throughout Egyptian history. Winged uraei dating from the Canaanite period have been found, proving that the image of the winged serpent was well known in ancient Israel.[2]

Scholar Karen Randolph Joines adds more to the Egyptian origin of this motif, by explaining that the usage of serpent images to defend against snakes was also an exclusively Egyptian notion without evidence in Canaan or Mesopotamia.[3]

But the important element of these snakes being flying serpents or even dragons with mythical background is reaffirmed in highly respected lexicons such as the Brown, Driver, Briggs Hebrew Lexicon.[4]

The final clause in Isaiah 30:7 likening Egypt’s punishment to the sea dragon Rahab lying dead in the desert is a further mythical serpentine connection, as the sea dragon represented chaos in the ancient Middle East.[5]

But the Bible and Egypt are not the only places where we read of flying serpents in the desert. Hans Wildeberger points out historical Assyrian king Esarhaddon’s description of flying serpents in his tenth campaign to Egypt in the seventh century B.C.

“A distance of 4 double-hours I marched over a territory covered with alum and mûṣu[-stone]. A distance of 4 double-hours in a journey of 2 days (there were) two-headed serpents [whose attack] (spelled) death—but I trampled (upon them) and marched on. A distance of 4 double-hours in a journey of 2 days (there were) green [animals] [Tr.: Borger: “serpents”] whose wings were batting. A distance of 4 double-hours in a journey of 2 days…”[6]

The Greek historian Herodotus wrote of “sacred” winged serpents and their connection to Egypt in his Histories:

There is a place in Arabia not far from the town of Buto where I went to learn about the winged serpents. When I arrived there, I saw innumerable bones and backbones of serpents… This place, where the backbones lay scattered, is where a narrow mountain pass opens into a great plain, which adjoins the plain of Egypt. Winged serpents are said to fly from Arabia at the beginning of spring, making for Egypt… The serpents are like water-snakes. Their wings are not feathered but very like the wings of a bat. I have now said enough concerning creatures that are sacred.[7]

The notion of flying serpents in the Bible as mythical versus historical is certainly debated among scholars, but this debate gives certain warrant to the imaginative usage of winged flying serpents appearing in Chronicles of the Nephilim.[8]

One comment on “Of Myth and the Bible – Part 9: Flying Fiery Serpents”

Comments are closed.