There is a passage in the New Testament, Acts 17, that tells the story of the apostle Paul preaching his message of good news to the Greek pagans on Mars Hill. I wrote in an article and in a book about how Paul actually subverts the Greco-Roman culture by retelling the ancient pagan Stoic narrative redefined through a Christian worldview. He was so familiar with pagan beliefs that he could quote them and even retell their narratives. That means he studied his culture in order to connect with it so that he could share with that culture the risen Jesus, whom he had encountered. He read their philosophy and knew their myths and cultural narratives. The passage begins with him telling the Athenians that he perceived they were a religious people, based on their altar for an unknown god amidst the many of the pantheon.

I feel like that when I watch Marvel movies such as Captain America: Civil War.

I perceive that America is a religious people. I don’t mean in the old sense of the “Christian America” origins or even the high percentage of American believers in that God. What I mean is that as Western society has become more secular and more Christophobic, it has correspondingly become, not less religious, but more pagan in its religiosity.

Case in point: Superheroes.*

Pagan religiosity is illustrated in the polytheistic embrace of this new pantheon of gods. It is not news that superheroes are modernized updated versions of ancient gods 2.0. Humanity craves transcendence and deity, and if we refuse the living god, we replace him with new gods, and a new religion. So even the secular reductionism of the modern superhero only serves to perpetuate religious myth in a “secular” pseudoscientific garb. Most superheroes have some kind of scientific origin for their powers. Even Thor is not supernatural, but merely an ancient alien.

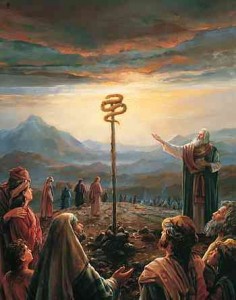

Romans 1:21–23

For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things.

The modern world rejects the living God and so it creates substitute gods and religions in order to tell stories that embody its values.

But in spite of this idolatry, and like Paul with the Stoics on Mars Hill, I am often amazed to find some powerful truths in the Marvel universe with which I would certainly want to agree.

One of those values is the American Exceptionalism of Captain America.

Movies are not made in a vacuum. They often reflect the zeitgeist or “spirit of the age” that permeates our culture. We are a polytheistic society that has become increasingly polarized in our political and cultural wars. Thus it is no surprise that our gods now express that internal hostility in such movies as Captain America: Civil War (CA:CW) and Batman Vs. Superman. As one of the characters says in CA:CW, “An empire that crumbles from its enemies can rise again, but if it crumbles from within, it is dead forever.” The villain in CA:CW seeks to get his enemies, the Avengers to kill each other.

But in contrast with the usual multicultural zeitgeist of Hollywood is Marvel’s apparent rejection of the socialist utopian madness that is gripping the minds of our society like the talons of a possessing demon. We have become cynical and nihilistic, thus, the perennially perfect good guy, Superman (Of the DC universe) has renounced his American citizenship in the comics, and turned dark along with the Dark Knight by Frank Miller (UPDATE: Correction on the Batman Vs. Superman movie).

But into this cynical world, comes the superhero from the past, Captain America. Quite literally, he is transported into our modern world from the old days of WWII. So he still has those quaint American values that Superman rejected in a previous movie (“Truth, Justice” but certainly no “American Way”). And that is what makes our modern cynical society willing to watch him, because they see it as outdated anachronistic and ironic in juxtaposition with our modern day. Oh, how cynics and nihilists love “irony.”

But it is just here that Cap becomes the lesson from the “greatest generation.” It is precisely those values of “outdated” left behind American Exceptionalism from a bygone era, an era usually damned as “Ozzie and Harriet” values, that becomes the goodness, integrity and righteousness that could save us from ourselves. The values of chivalry that seems arrogant and presumptuous to modern left wing collectivism and the so-called anti-colonialism of Obama’s America.

I won’t pretend to understand all the mythic trails of the Marvel universe, nor remember all the tedious details of their mythology and characters. But the big picture story of Captain America: Civil War is that the world is blaming the Avengers for all the destruction that has occurred because of the terror activities of Hydra’s bad guys who want to control the world. Hmmmm, does that sound like America being blamed while protecting the world from a certain extreme wing of a certain religion we all know is performing jihad in the name of their god? And while we are at it, let’s throw in the atheist religion of communism that still threatens the globe. So these bad guys are so evil, they cause great swathes of destruction as the Avengers fight to stop them. Entire cities wiped out, innocent lives lost, the usual collateral damage that totalitarian regimes cause when stood up to.

And yet, the world blames the Avengers for it! WTF? The Avengers are accused of “routinely ignoring sovereign borders” as if they are global bullies engaging in macroagressions rather than saving everyone’s asses. (Quick, where is the safe space with playdoh and crayons?!)

As the Vision, who is supposed to be very intelligent AI, very stupidly says, “Our very strength invites challenge, and challenge breeds hostility.” This blaming of the victim is the very heart and soul of the left wing Anti-Americanism that is destroying our country from within. It is a collectivism that doesn’t understand the nature of evil. It is not strength that breeds or invites hostility, it is weakness that does. Bullies don’t pick on the strong, they pick on the weak. Communist countries, and Islamic terrorists “vote for the strong horse.” They will only stop when forced to stop — by strength.

Captain America understands the nature of evil, and the nature of American Exceptionalism. He says, “When you can do the things we can, but you don’t, then bad things happen because of what you didn’t do.” When America pulls out, evil grows to fill that void.

But the world blames the good guys, and seeks to have them sign a treaty of “accords” that would place the Avengers under the authority of the United Nations, to be more collectively accountable. Think of it as redistribution of power. Funny how the greed of envy works, isn’t it? Legalizing theft and crybullying.

It is here that the movie seeks to have a dialectic between collectivism and individualism. Some of the Avengers turn wimps (led by the chief cynic, Iron Man. Hmmmm, any surprise, the most cynical becomes the first fooled?), and they split between two camps of Avengers, those who seek to sign the accords and appease the envy and greed of morally inferior debtor nations, and those led by Cap, who has “faith in individuals,” and a strong moral compass to be leaders in righteous strength.

The appeaser Avengers “do what has to be done to stave off something worse,” and in so doing, actually make matters worse, precisely because that collective authority (the UN) under whom they place themselves is morally inferior.

It is here that the movie becomes fallacious in depicting the UN as a neutral body of nations who just want to have peace and order, when in reality, it is a corrupt body of greedy and immoral criminals (See the documentary U.N. Me). But I get it, they want to show both sides at their best in order to have a “balanced” dialectic.

But the true moral superiority of Captain America and his Americanism shines when he says he won’t sign the accords because it keeps them from fighting evil, which makes evil win. As he says, “When I see a situation going south, I can’t ignore it,” and “Even if the whole world tells you something is wrong when it is right, you say, No.” This is how a righteous man thinks, a moral man, a strong protector of the weak.

But this is not a naïve self image that ignores America’s faults or imperfections. No nation is perfect, and certainly not America, but it’s the best we’ve got. As Cap says, “We may not be perfect, but the safest heads are our own.” American Exceptionalism is not “my country, right or wrong,” but it’s also not the moral relativism of multiculturalism that concludes that our morality is no better than any other country’s morality. Moral fools propound moral equivalence.

The collectivism of the United Nations does not create peace, it creates war, by tearing down the strength of the righteous just like it did to the Avengers. The selfish greedy thievery of socialist redistribution does not create wealth, it destroys it. The oppression of human rights and genocidal impulse of Islamic states is not the equivalent of the Judeo-Christian chivalry and self-sacrifice of the West. There is right and wrong, and some cultures are wrong. Cap believes we must lead by strength and righteousness, which will be the model and example for morally inferior nations to aspire to.

That is what made America great.

And that is what makes Captain America the coolest of all the Avengers and the victor in the inevitable civil war of Avengers at the end.

Nevertheless, like Paul on Mars Hill, I have to say that despite some of these positive truths portrayed in CA:CW, I find myself unsatisfied by the substitute pantheon for the living God. For only with the Judeo-Christian God can there be any intelligibility to the chivalric values of righteous strength. Without God, even American Exceptionalism is hollow idolatry. Without a transcendent God, all values are morally equivalent as the godless and nihilist argue. One man’s superhero is another man’s supervillain. Without God, there is no righteous nation, just nations and their gods vying for power — and the will to power rules.

Without the one God of the Bible, there is no justice, there is only war.

* Another example of the spreading influence of paganism is Environmentalism and the Climate Change Cult that is sweeping over nations like a global Crusade. It is a return to pagan earth worship with a fascist religious regime akin to the Inquisition, complete with high priests, punishment for heretics and End of the World threats.