In Matthew 16:13-20 is the famous story of Peter’s confession of Jesus as the Christ, who then responds, “I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (v. 18). Shortly after, Jesus leads them up to a high mountain where he is transfigured.

First off, let’s get this straight. It isn’t “Hell” whose gates Jesus is talking about, but Hades, a very different thing than what most people think. The Greek words are actually “Gates of Hades,” which is not a place of eternal burning fire, but rather the temporary holding place of dead souls before the judgment. It was the Abode of the Dead. (More on that in future posts)

In order to understand the spiritual reality of what is going on in this polemical sequence and its relevance to the cosmic War of the Seed, we must first understand where it is going on.

Verse 13 says that Peter’s confession takes place in the district of Caesarea Philippi. This city was in the heart of Bashan on a rocky terrace in the foothills of Mount Hermon. This was the celebrated location of the grotto of Banias or Panias, where the satyr goat god Pan was worshipped and from where the mouth of the Jordan river flowed. This very location was what was known as the “gates of Hades,” the underworld abode of dead souls.

The Jewish historian Josephus wrote of this sacred grotto during his time, “a dark cave opens itself; within which there is a horrible precipice, that descends abruptly to a vast depth; it contains a mighty quantity of water, which is immovable; and when anybody lets down anything to measure the depth of the earth beneath the water, no length of cord is sufficient to reach it.”[1] (this cavern shows up in the new novel, Jesus Triumphant)

As scholar Judd Burton points out, this is a kind of ground zero for the gods against whom Jesus was fighting his cosmic spiritual war. Mount Hermon was the location where the Watchers came to earth, led their rebellion and miscegenation, which birthed the Nephilim (1 Enoch 13:7-10). It was their headquarters, in Bashan, the place of the Serpent, where Azazel may have been worshipped before Pan as a desert goat idol.[2]

When Jesus speaks of building his church upon a rock, it was more of a polemical contrast with the pagan city upon the rock, than it may have been a word play off of Peter’s name, meaning “stone.” In the ancient world, mountains were not only a gateway between heaven, earth, and the underworld, but also the habitations of the gods that represented their heavenly power and authority.[3]

The mountain before them, Hermon, was considered the heavenly habitation of Canaanite gods as well as the very Watchers before whose gates of Hades Jesus now stood.

The polemics become clearer when one realizes that gates are not offensive weapons, but defensive means. Christ’s kingship is storming the very gates of Hades/Sheol in the heart of darkness and he will build his cosmic holy mountain upon its ruins.[4]

But the battle is only beginning. Because the very next incident that occurs is the transfiguration (Matt. 17:1-13).

The text says that Jesus led three disciples up a high mountain. But it doesn’t say which mountain. Though tradition has sometimes concluded it was Mount Tabor, a more likely candidate is Mount Hermon itself. The reasons are because Tabor is not a high mountain at only 1800 feet compared to Hermon’s 9000 feet height, and Tabor was a well traveled location which would not allow Jesus to be alone with his disciples (17:1).[5]

Then the text says, that Jesus “was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became white as light. And behold, there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him” (Matthew 17:2–3). When Peter offers to put up three tabernacles for each of his heroes, he hears a voice from the cloud say, “This is my beloved Son with whom I am well pleased, listen to him” (vs. 4-5).

The theological point of this being that Moses and Elijah are the representatives of the Old Covenant, summed up as the Law (Moses) and the Prophets (Elijah), but Jesus is the anointed King (Messiah) that both Law and Prophets pointed toward.

So God is anointing Jesus and transferring all covenantal authority to him as God’s own Son. And for what purpose? To become king upon the new cosmic mountain that God was establishing: Mount Zion in the city of God. But wait, didn’t you read me say he would build it upon Hermon? Follow me, here…

In the Mosaic Covenant, Mount Sinai was considered the cosmic mountain of God where God had his assembly of divine holy ones (Deut. 33:2-3). But now, as pronounced by the prophets, that mountain was being transferred out of the wilderness wandering into a new home in the Promised Land as Mount Zion (ultimately in Jerusalem).

And that new mountain was the displacement and replacement of the previous divine occupants of Mount Hermon. Of course, just like David the messianic type, Jesus was anointed as king, but there would be a delay of time before he would take that rightful throne because he had some Goliaths yet to conquer.

Take a look at this Psalm and see how the language of cosmic war against the anointed Messiah is portrayed as a victory of God establishing his new cosmic mountain. We see a repeat of the language of Jesus’ transfiguration at Hermon.

Psalm 2:1–8 (NASB95)

Why are the nations in an uproar And the peoples devising a vain thing? The kings of the earth take their stand And the rulers [heavenly as well?] take counsel together Against the Lord and against His Anointed [Messiah], saying, “Let us tear their fetters apart And cast away their cords from us!” He who sits in the heavens laughs, The Lord scoffs at them. Then He will speak to them in His anger And terrify them in His fury, saying, “But as for Me, I have installed My King Upon Zion, My holy mountain.” “I will surely tell of the decree of the Lord: He said to Me, ‘You are My Son, Today I have begotten You. ‘Ask of Me, and I will surely give the nations as Your inheritance, And the very ends of the earth as Your possession.[6]

Like Moses’ transfiguration in Exodus 34:29, Jesus’ body was transformed by his anointing to shine with the glory of those who surround God’s throne, evidence of divine status (Dan. 10:6; Ezek 1:14-16, 21ff.; 10:9).[7]

But that description is no where near the ending of this spiritual parade of triumph being previewed in God’s Word. One last passage illustrates the conquering change of ownership of the cosmic mountain in Bashan. Notice the ironic language used of Bashan as God’s mountain, and the spiritual warfare imagery of its replacement.

Psalm 68:15–22

O mountain of God, mountain of Bashan; O many-peaked mountain, mountain of Bashan! Why do you look with hatred, O many-peaked mountain, at the mount that God desired for his abode, yes, where the Lord will dwell forever? The chariots of God are twice ten thousand, thousands upon thousands; the Lord is among them; Sinai is now in the sanctuary. You ascended on high, leading a host of captives in your train and receiving gifts among men, even among the rebellious, that the Lord God may dwell there… But God will strike the heads of his enemies, the hairy crown of him who walks in his guilty ways. The Lord said, “I will bring them back from Bashan, I will bring them back from the depths of the sea.

In this Psalm, God takes ownership of Bashan with his heavenly host of warriors, but then replaces it and refers to Sinai (soon to be Zion). It is not that God is making Bashan his mountain literally, but conquering its divinities and theologically replacing it with his new cosmic mountain elsewhere.

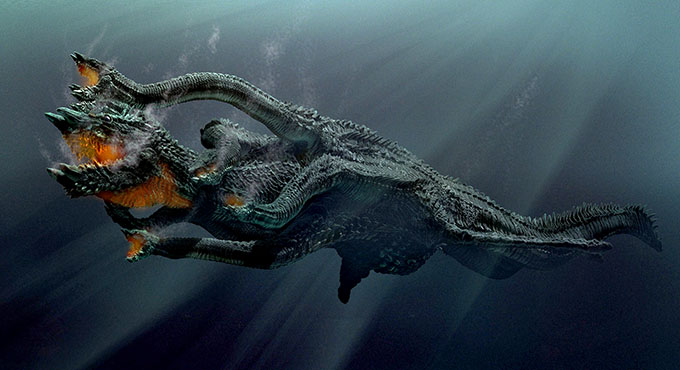

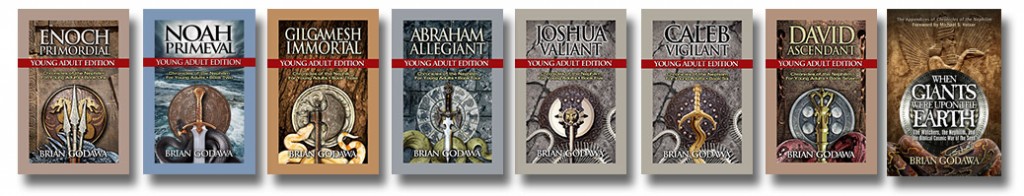

In verse 18 we see a foreshadowing of Christ’s own victorious heavenly ascension, where he leads captives in triumphal procession and receives tribute from them as spoils of war (v. 18). He will own and live where once the rebellious ruled (v. 18). He strikes the “hairy crown” (seir) of the people of that area (v. 21), the descendants of the cursed hairy Esau/Seir,[8] who worshipped the goat demons (as depicted in Joshua Valiant and Caleb Vigilant).[9] He will bring them all out from the sea of chaos, that wilderness where Leviathan reigns.[10]

But first, the Messiah must descend into that sea to claim his victory.

And that “sea” of descent is Hades. Stay tuned in the next post as we talk about Christ’s descent into Hades.

For additional Biblical and historical research related to this novel, go to www.ChroniclesoftheNephilim.com under the menu listing, “Links” > Jesus Triumphant.