The story of the Mayflower’s arrival in America in 1620 and the civilization that began from it.

I saw an advance screening of the dramatic narrative mini-series called Saints and Strangers. If you want to bring a fresh and inspirational understanding to your Thanksgiving holiday, then you must catch this two part series starting November 22 on the National Geographic Channel. It was informative, riveting, and truthful. I teared up with encouragement at some of the moments of faith and righteousness depicted in this film.

Leave it to South Africa and unknown writers and directors to create a faithful, fair and nuanced portrayal of the origins of American civilization, because Hollywood probably couldn’t do it without a hate spin against Judeo-Christianity and western civilization.

As it is, this story is rich and layered with flawed humanity and high aspirations of transcendence and righteousness. About 130 souls arrive on the shores of the New World in the Mayflower. Not all were religious separatists seeking asylum from religious oppression in England. There were others more secular, yet governed by Judeo-Christian notions of civilization. So the story is rife with dramatic tension between the believers and unbelievers who debate quite openly about their understanding of God and divine providence. Not the religious fanatics you were taught in school and college.

For those not familiar with the history, Saints and Strangers charts their journey from the ocean trip to their landing, settling, meeting the indigenous tribes, facing near obliteration by starvation, rescue by Squanto, as well as the fears, conflicts, and reconciliation with the Native American tribes.

First off, the portrayal of faith in this story is fair and truthful, but also honest and nuanced. The saints certainly start out sounding like strangers to our modern ears with their dedication to Christian values. And they are not perfect nor sinless. But the depiction of their fears, failures and moral struggles maintains the dignity of their faith thoughout the entire story.

They steal corn from one of the native tribes’ storage areas, which brings about hostility. But they did so understandably from starvation and the need to survive. The Pilgrims later apologize to the tribe and even offer restoration for their behavior. This isn’t modern Leftist reparations of theft and forced redistribution of distant ancestors’ wealth. This is Biblical restoration of taking responsibility for one’s own actions and repaying those directly affected by an offense.

William Bradford, the longtime governor of the colony, was amazingly portrayed with integrity as a godly man of faith who sought God’s righteousness as well as peace with the native tribes. But he is not condescending of the unbelievers in their group or the locals, nor is he self-righteous. He struggles over the need to defend themselves against savage attacks, and the need to apply corporal punishment to maintain authority and civilization. And all in submission to God’s ways. He chooses the right path most of the time, but not without its price on such a righteous soul. I have not seen such a truthful portrayal of a good and godly yet imperfect man in a long time. Because of Bradford’s Christian charity in tending to the native wounded after a battle (against the wishes of the secularists), that tribe finally decides to accept peace. Bradford is no pacifist, but he is no warmonger. He is a godly man who struggles to do what is right. But what is right is not always amenable to secular or pagan understanding.

This story is not a “whitewashing” nor is it a hit piece. And that’s what makes the faith in the story so powerful. Because it faces reality, admits weakness, but ultimately elevates the value of faith in God and the need for transcendence.

The portrayal of this single Christian character, Bradford, as flawed but ultimately heroic and just is a truly righteous feat of originality in an American story world that seems dominated by corrupt anti-heroes, nihilist darkness and Christophobia. Since Christians aren’t allowed representation as a Hollywood victim group, we’ll just have to make our voice known by supporting shows like this.

Probably the most powerful moment for me captured the essence of these pilgrims. At a particular time when the settlers are starving (eventually, they will humbly receive help from Squanto about agriculture), one of the men says to a woman, that with the death of one of the best men, Winslow, his purpose has died with him. The woman schools the faithless man, (and I quote) “Not so. It is the service of the divine that gives us both purpose and salvation. I am alone, but I have the Lord, and so I have purpose. Everyone else can vanish in an instant, but He is constant.”

WOW.

I have chills writing that. And I cried when I watched it. Especially in its brutal context that we have been experiencing with these courageous souls.

But there were many perspectives in this fledgling community, and all views were given voice in this story in a fair way, as they all struggled to survive, Christian and secularist alike. But also the native tribes…

Anyone acquainted with real history and the truth of human nature will know that the Native American tribes were just as human all too human as everyone else. And the honest portrayal of the tribes in this story is no less honest than the portrayal of the Christians and Europeans. In a way, Saints and Strangers is a brilliant title because everyone in the story considers themselves the saints and the others to be strangers, including the pagans and secularists.

The tribes understandably react with hostility when the westerners steal their corn, but they too have their own failures of bigotry and self-righteousness in the process. Their ethic is power and while they school the Pilgrims in survival, the Pilgrims school them in grace. We are given an inside view of the politics of the tribes who are jockeying for status, manipulative, power hungry and even just as “self-superior” as every other human tribe on earth. There are good tribesmen and bad tribesmen, just as there are good westerners and bad westerners. Heck, some of natives are actually complex real humans who don’t fall into simple categories. But this isn’t moral equivalency either. Some tribes were more peaceful and others really were savages. All this is depicted fairly and accurately in Saints and Strangers.

This is not the Left Wing bigotry and anti-colonialist neo-Marxist agenda that divides the New World into the black and white categories of Native/pagan: Good, European/Judeo-Christian: Bad.

There is a moment when one of the Indians mentions that this is “their land,” as if they own it because they were there first. But this view isn’t validated in the story. It’s fair to depict that view because some no doubt believed it (even though the Native Americans lacked a substantial view of land ownership), but it certainly has no support from an evolutionary worldview of the Great Chain of Being and survival of the fittest. And without the Christian God, “first come = ownership” remains an unsupportable arbitrary claim of power. Without a true transcendent standard, there is no such thing as “ownership,” there is only the Will to Power.

But I digress philosophically.

Squanto, because of his peculiar journey of being kidnapped, enslaved, but then redeemed by the “white man,” is a prime influence on communication between the strangers. Of all men, he would have been most likely to hate the European crackers, but he does not. He brings them together. Yet, even he is depicted as having questionable motives at times, a complex character, more like real history than legend. It is here that multiculturalists will find their hero, as if Squanto represents the reconciliation through non-judgmental unity with other cultures. But I see him more as a Christian convert who has encountered a superior God and civilization and seeks to keep his people from being destroyed by their own backwardness and ignorance.

If typical “Hollywood” types would have made this picture, the Pilgrims would have been Westboro Baptist colonialist imperialists, Indian killers who came to achieve genocide with disease, and take the land away from the Native Americans who were peace-loving environmentalists at one with nature and superior to the barbarism of western Judeo-Christian culture. This historical moment would be a microcosm of the source of our own modern day polarity of separation and hatred and violence, with our only hope being a return to the pagan earth god.

Thank God for the South Africans.

One thing not made clear in the story is that the “Separatists” were not people who withdrew from society because of religious fear of the “other.” They were called Separatists because they believed in their right to worship separately from the Church of England. That is a subtle but very important difference that modern day anti-religious bigots do not grasp. Their “separatism” was for religious freedom, not moral self-righteousness.

Despite all my praise for the depiction of Christianity in this story, there is a voice for the secular multiculturalist as well. The character who changes the most in the story is the secular Stephen Hopkins, who starts out a selfish greedy exploiter, but ends up apologizing to the natives, and regretting “taking their land, stepping on their gods, and glorifying ours.” He even gives the standard moral equivalency line, “Whose to say who the savages are. I used to see black and white, now everything is gray.” But that’s okay. I only ask for a fair portrayal of Christianity within that complex world of views. Life isn’t always black and white, and there is some truth in the claim that we all share the same fallen nature within the right context. I think this story provides that proper context because in the end, it is the Christian values of humility, respect for law and authority, grace, and redemption that bring about the salvation and reconciliation within and between the communities.

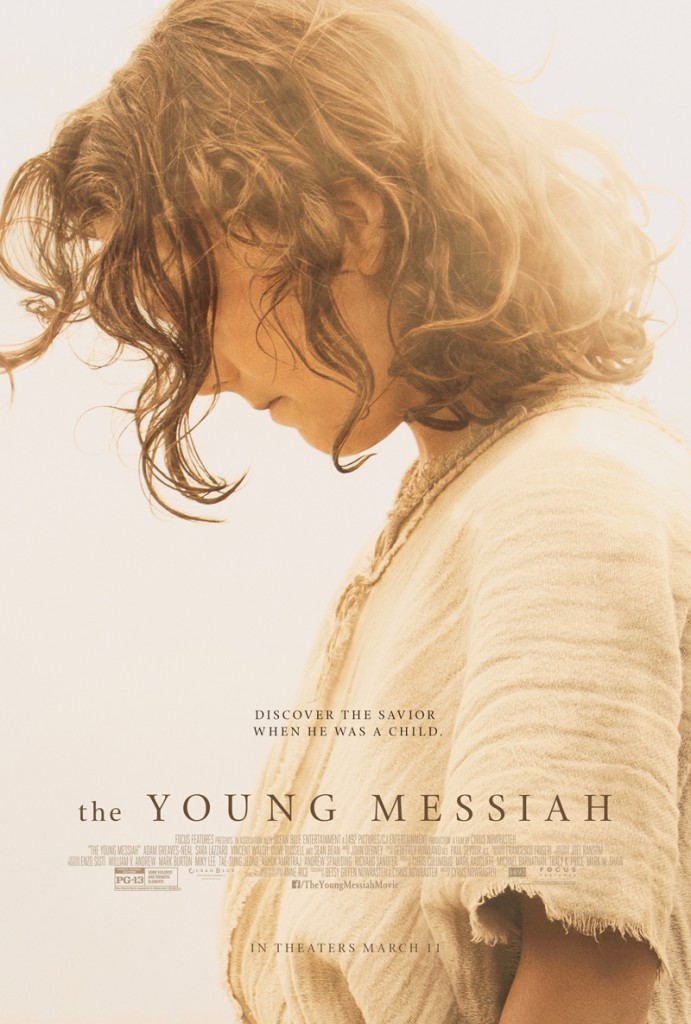

The Blu-Ray and DVD release of The Young Messiah is today and I want to encourage all those viewers who want more quality Christian movies or faith friendly or family friendly or values friendly movies to support this release.

The Blu-Ray and DVD release of The Young Messiah is today and I want to encourage all those viewers who want more quality Christian movies or faith friendly or family friendly or values friendly movies to support this release.