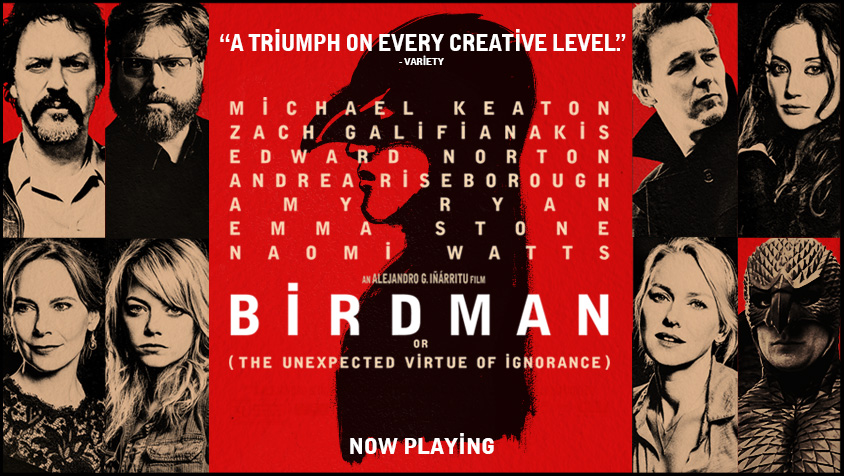

The story of Alan Turing, the brilliant yet troubled mathematician who led the cryptographic team that defeated the Nazi Enigma code in WWII and created the world’s first computer.

Wow, this Oscar season offers a slew of amazing performances. This one by Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing is a riveting and pathos filled drama that views like a gay version of the Oscar winning A Beautiful Mind.

This movie is a riveting, solid, well-told story. Brilliant in its machinations and exciting in its imagination. It explores the nuance of moral decisions in war, the complexity of social classes and issues, the alienation of mental illness, and the pain and irony of genius.

Who could have thought that there could be such exciting suspense, such heart-stirring pity, and such powerful moments of cheerful dramatic victories in a movie about a group of weird nerds penciling out mathematics and building a computer? But The Imitation Game is all that.

And it’s a brilliant artistic masterpiece for the homosexual agenda.

Many conservatives and religious folk have said that the homosexual element is minor and not what the movie is really about. They have missed the point entirely and have become victims of good storytelling, no, great storytelling.

Let me explain how this works.

A great story is able to link, by analogy, a personal journey to a larger societal or historical issue that both connect by analogy to a broader universal theme. For instance, A Beautiful Mind told the story of Nobel Peace Prize winning mathematician John Nash (also, an asocial type like Turing), whose brilliant work in cryptography, coupled with his schizophrenic mental illness, became a metaphor for the universal theme of the modernist rational quest for truth and the romantic humanist desire for love and meaning. His mind’s limitations caused delusions of paranoia, but the heart has its reasons that the mind knows not of. It’s Cold War subtheme of paranoia was historically timely in that the movie was released in a post-9/11 world. John’s own personal psychological struggle with discerning reality from illusion was an incarnation of our modernist quest to discern truth from fiction, and real from imagined enemies. His personal struggle with his mental illness was a perfect metaphor for a philosophical and social issue.

A great story is able to link, by analogy, a personal journey to a larger societal or historical issue that both connect by analogy to a broader universal theme. For instance, A Beautiful Mind told the story of Nobel Peace Prize winning mathematician John Nash (also, an asocial type like Turing), whose brilliant work in cryptography, coupled with his schizophrenic mental illness, became a metaphor for the universal theme of the modernist rational quest for truth and the romantic humanist desire for love and meaning. His mind’s limitations caused delusions of paranoia, but the heart has its reasons that the mind knows not of. It’s Cold War subtheme of paranoia was historically timely in that the movie was released in a post-9/11 world. John’s own personal psychological struggle with discerning reality from illusion was an incarnation of our modernist quest to discern truth from fiction, and real from imagined enemies. His personal struggle with his mental illness was a perfect metaphor for a philosophical and social issue.

The Imitation Game is a similar timely metaphor. It tells the story of an oddball man who was rejected by the very society that he saved because of his genius. A tragedy of greatness. It is about breaking down our personal and social prejudices by showing that the very kind of people we often reject are the ones who do great things, such as, oh, save the world. History definitely bears out the repeated theme of the movie, “Sometimes, it’s the very people that no one imagines anything of that do the things no one can imagine.” Society too often rejects the misfits, who may offer the most to bring balance to the world. And who of us doesn’t at some time in our lives feel like such misfits and oddballs who feel out of place?

Let the spin games begin.

Storytelling does not make logical arguments so much as emotional arguments. It incarnates logic or worldviews which touches us existentially as storied human beings. Story makes its most powerful connections emotionally through such rhetorical techniques as montage. The concept is that by placing two or more disparate images or storylines next to each other, viewers make emotional connections between those things, whether or not they are logically connected.

In The Imitation Game, the story addresses social “inequities” most of us would not dispute. It deals with the unfair repression of women in the workforce and society. Keira Knightley’s character, and closest friend of Alan, Joan, is shown as being smarter than all the boys, while being given short shrift in society. She isn’t allowed to work with only men, her parents pressure her to get married instead of becoming a working woman. These are all the classic feminist arguments neatly packaged into a perfect victim that only a Blue Meanie would not sympathize with.

Then, it shows us Alan’s alleged autistic Asperger’s type social awkwardness. Well, who among us would not feel sorry for such innocent suffering? The poor guy can’t help it, and he’s really quite sweet underneath that rudeness and lack of emotion and sensitivity. Heck, understanding people is like cracking a code for him. And of course, it is precisely that autism that blesses him with the mathematical brilliance to break the Enigma code of the Germans that ended the war early and saved millions of lives. But that is not all. That autism that we would see as “abnormal” resulted in figuring out the world’s first computer, one of mankind’s greatest achievements.

So, you can see the litany of injustices that are laid out, with which the viewers could not disagree. Civil rights of women, unjust stigma of mental illness, the revenge of the nerds.

Americans are suckers for the underdog. If you want to engender sympathy for a character, make them suffer persecution, unfairness, injustice. In other words, make them a victim. The ultimate power of the extreme violence of the The Passion of the Christ was that it basically made Jesus the most unjustly brutalized victim in the history of cinema. Which is really necessary since the point was to make him the savior of the world through suffering, so Gibson had to maximize that suffering to make the emotional connection in the viewer with the grandiosity of the redemption. This is why many liberals, in a fit of outright contradiction, hated The Passion as being “obsessively gory” but fully embraced the equal brutality of 12 Years a Slave as being “redemptive,” though both movies were doing the exact same thing. Because such viewers do not want to give religion the same redemptive power as race.

The thematic cleverness of The Imitation Game lies in its montage connection of Turing’s homosexuality with his genius and with all these other civil rights issues with which we have all come to agree upon. The movie creates a touching tragic homosexual love story from Turing’s past to show his deep pain of loss. And then it lays it on heavy with a bookend story of Turing’s tragic arrest and conviction of his homosexual acts in a time and place in British history where it was illegal. Who wouldn’t feel sorry for the suffering of chemical castration that he had to endure as a legal penalty? Again, more victimization, more emotional sympathy.

It will never occur to many viewers that there is no rational justification for claiming sexual behavior as an innate civil right, that there is no logical or rational connection between Turing’s homosexuality and his genius, his saving the world, or other civil rights protections. There doesn’t have to be. An emotional connection was made through montage and analogy, and that is just as powerful on the viewer’s psyche. Emotionally, the viewer feels the connection of Turing’s homosexual identity with greatness and with saving the world. The irrational, yet emotional conclusion is that to be against homosexuality is to be against greatness and saving the world.

This is the very reason why homosexual activists have been successfully commandeering school curriculums across the US to teach historical “contributions of homosexuals.” Even though their sexuality has nothing to do with their achievements, by emphasizing that identity through indoctrination, they will emotionally manipulate society to accept it as normal, or be ostracized as homophobic bigoted haters who will stop great achievements from saving the world simply by disagreeing with the morality of homosexuality. No logical or rational arguments are allowed.

Coded messages are creatively embedded in the story to subvert the viewer though analogy. Here’s how its done. The storyteller makes an argument with which the viewer agrees, by using phrases that are common with an argument with which the viewer may not agree. So, when Alan is explaining how machines and human minds are different, he says, “The question is, just because a machine thinks differently than you, does that mean it is not thinking? We allow such differences with humans. He have different tastes, different preferences. Our brains work differently.” Though these statements are about one area of scientific differences, they clearly reflect the common framing of the homosexual debate as “sexual preferences” rather than sexual morals, and the already discredited attempt to say brains of homosexuals are different by nature. You know, “born this way.” In this way, emotions can persuade contrary to the facts and reason.

Coded messages are creatively embedded in the story to subvert the viewer though analogy. Here’s how its done. The storyteller makes an argument with which the viewer agrees, by using phrases that are common with an argument with which the viewer may not agree. So, when Alan is explaining how machines and human minds are different, he says, “The question is, just because a machine thinks differently than you, does that mean it is not thinking? We allow such differences with humans. He have different tastes, different preferences. Our brains work differently.” Though these statements are about one area of scientific differences, they clearly reflect the common framing of the homosexual debate as “sexual preferences” rather than sexual morals, and the already discredited attempt to say brains of homosexuals are different by nature. You know, “born this way.” In this way, emotions can persuade contrary to the facts and reason.

The ultimate argument for normalizing homosexuality is the complete deconstruction of “normal,” to the point where people have contempt for “normality” by spinning it as being unrealistic, even destructive. At the end of The Imitation Game, Alan is depressed and envious of Joan’s “normal life.” But she then says that no one normal could have done what he did. She explains a litany of things like trains and tunnels and people that would not exist if it were not for him saving the world through decoding Enigma. She says, “If you wish you were normal, I can say that I certainly do not. The world is an infinitely better place precisely because you weren’t normal.”

A detective who figured out Alan’s secret sex life, after hearing his story of decoding Enigma, says, “I can’t judge you.”

So, now the emotional connection is reinforced between “judging” (that nasty evil word in our multiculty world) and “normality” (that wicked evil claim of Christians about sexuality). Really, this becomes a subversive intolerance and hatred of normal as evil.

Rational arguments are neatly subverted by the power of emotional ones in this beautifully crafted masterpiece of emotional montage. It’s really quite impressive propaganda. I think Christians could learn a thing or two from it that they should apply to their shabbily crafted celluloid sermons.

But there is another comparison with Christians and homosexuals in this world war of stories. The victimization of the homosexual in The Imitation Game is exactly reversed in the movie, Unbroken, about the Christian Louis Zamperini and his suffering as a WWII POW. It really typifies the reversal of what I think is going on in our culture where those who disagree with homosexual practice are now being targeted for their identities and oppressed through social bigotry and Christophobia (businesses and careers destroyed, smear campaigns of hate). In The Imitation Game, the homosexual identity is connected with the story of greatness, while in Unbroken, the Christian identity is disconnected from the story of greatness.

And who is the one whose identity is being oppressed?