Okay, it wasn’t like a Damascus Road Zap, more of a culmination of a long journey ending in this movie.

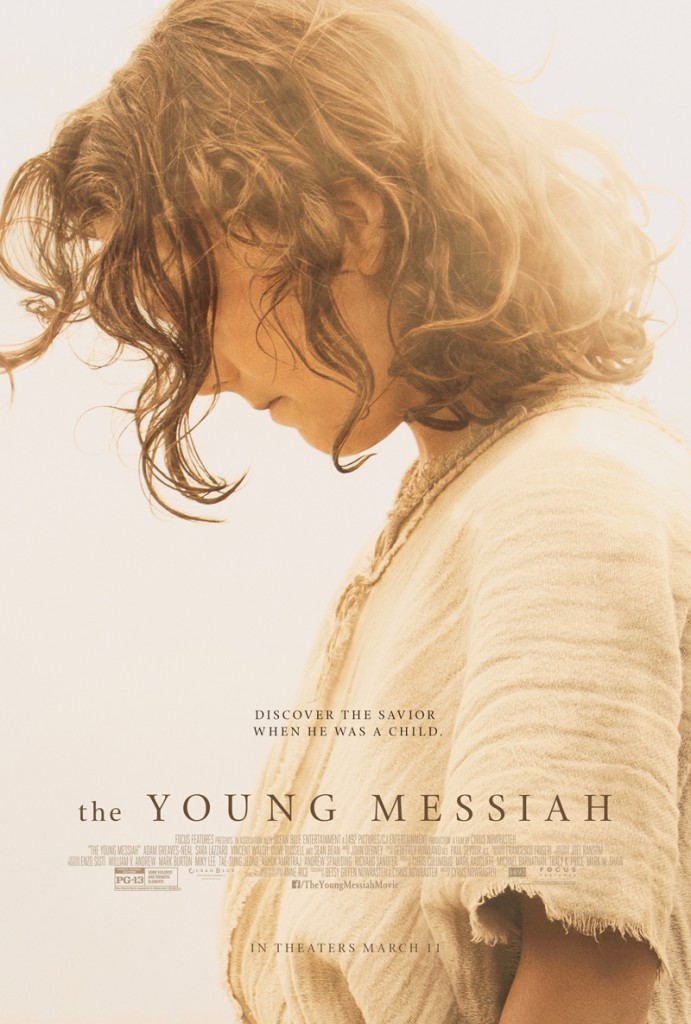

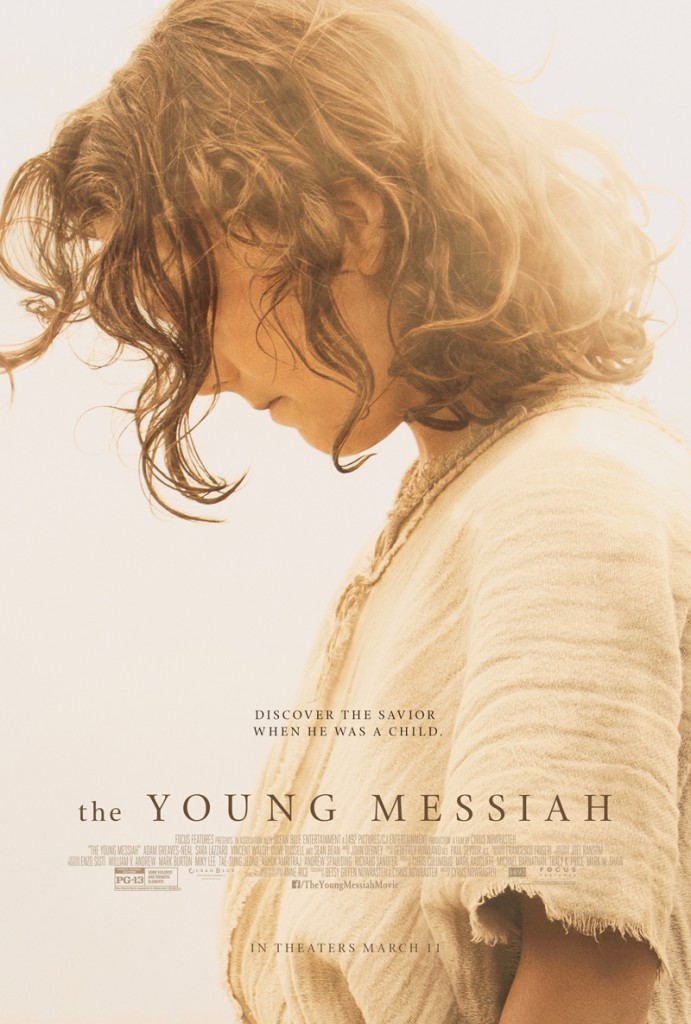

I got to interview Cyrus Nowrasteh about the upcoming movie, The Young Messiah, that opens March 11. You HAVE to see this movie. It’s a thoughtful and dramatic exploration of Jesus and his human coming of age as the Son of God.

You can read my review of the movie here.

It opens next Friday, March 11.

Here is the interview…

Brian: Tell me about the Genesis of this project and its journey to the screen.

Cyrus: I remember having dinner in 2005 with my agent at CAA. He talked about his client Anne Rice coming out with a book called Christ the Lord, that is going to blow everyone’s mind, because at the time, she became born again, or whatever you want to call it. I thought it was a fresh and original take on Jesus, focusing on him entirely as a seven-year old child.

If you told me then, about 10 years ago, that I’d be making a movie from that book, I’d have told you you were on crack. For a slew of reasons. But [my movie] Stoning of Soraya M. came out in 2009. Anne Rice wrote a rave review of it. So I called the same agent. She thought I’d be perfect for it. I read it and fell in love with it. I contacted Chris Columbus’ 1492 Pictures. I worked with them in the past. They optioned the book, and developed the script with me attached to direct.

B: So it took over 10 years to get made. And that’s just the beginning of the miraculous things that would happen. What were the reasons that made you hesitate from making the movie at first?

C: First of all, she’s very prominent. She’s been writing best-sellers for over 40 years. She’s had movies made from her books. And her books are very expensive to acquire and get made. That was one reason. The other was what it was about. I had been on my own journey towards Christ for a long time, probably longer than I even know. But I certainly didn’t think I was prepared to tackle a project about Jesus, much less a very risky and challenging one, taking on a portion of his life that is considered the silent years. I knew that would be controversial.

Writer-Director Cyrus Nowrasteh

B: What unique issues did you face in adapting this book to a film?

C: She did a very challenging thing in the book. It was pretty gutsy. The entire book is written in the first person voice of Jesus. That was challenge number one. The other challenges were theological. Anne grew up Catholic. I didn’t know it at the time, that she used a lot of other sources. Some of them are apocryphal, and some of them are legends that come down about the childhood of Jesus in the vicinity of Alexandria going back 2000 years. The Coptic Christians still tell these stories about Jesus. She used everything and anything that she could find. And we felt, Betsy (wife and co-writer) and myself, that if we were going to write it, that we were going to have to reexamine those issues. We are not theologians or scholars. It was through multiple drafts, having friends and associates, theologians, people who we trusted, who came back with feedback. It took time for us to figure out how we could navigate those issues and still tell the story in a dramatic and compelling fashion.

[BG DISCLOSURE: I was one of those who read the script early on. To be honest, I knew Christians would not like it at that point in its development, because of some of the material they included. But as you read on, you’ll see how he and his wife co-writer changed it because of their spiritual journey. Good news! this movie is now totally Biblically consistent, even though it obviously takes creative license. I loved it.] Read on to see what happened… Continue reading →